HARMONIC EXPANSIONS

CHAPTER 4: INSERTING PRE-DOMINANTS AND THE CIRCLE PROGRESSION

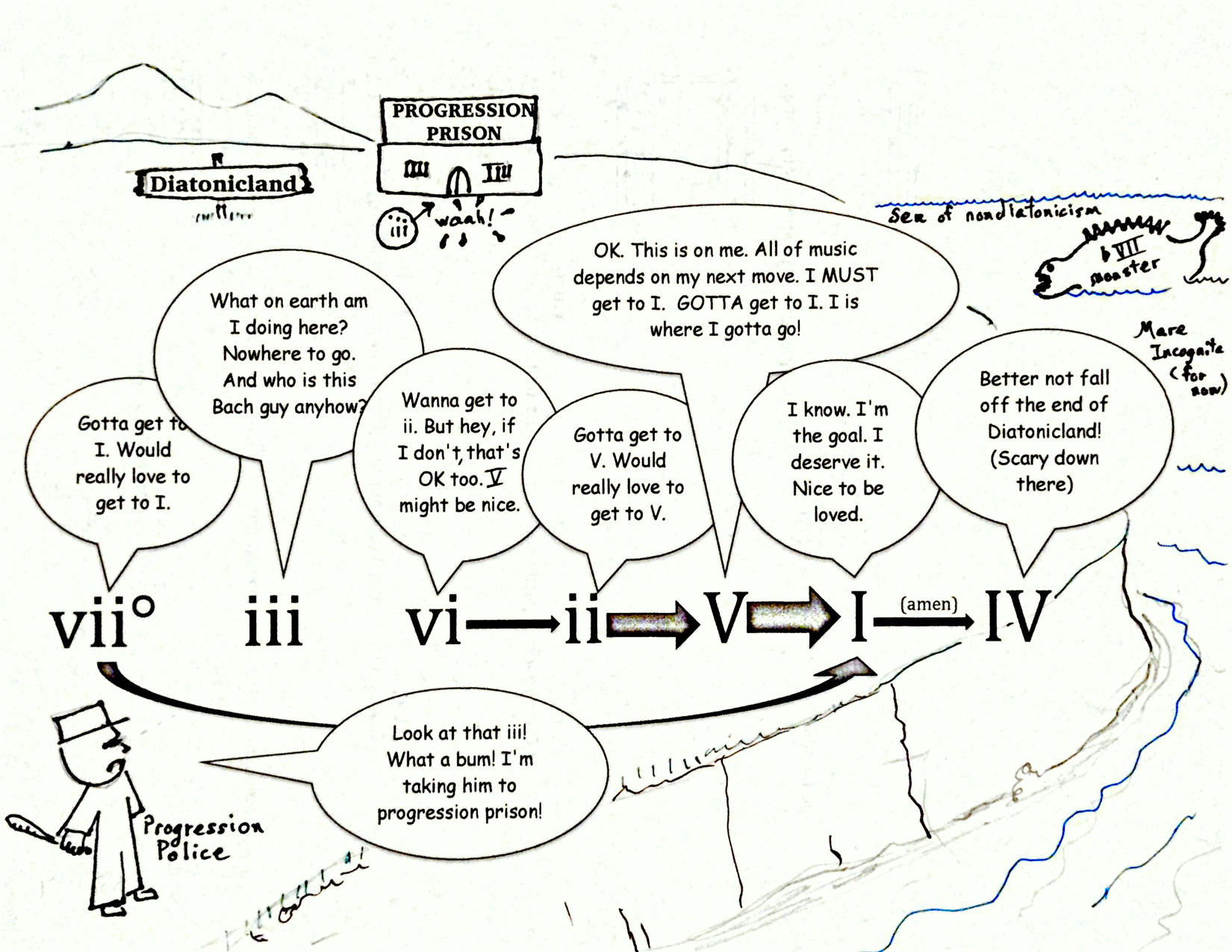

4.7 Limits on the sequence of chords in circle progressions

|

|

|

|

|

Why do circle progressions tend to begin on vi and end on I? If chords tend to follow the circle of fifths counterclockwise what is to prevent the progression from going around the circle forever and never stopping at all? Well, stopping at I can be explained by the fact that I is the most stable chord in any key, and that the V - I progression at the end of a piece is an expectation which is basic to western music--as represented by the fundamental harmonic progression. In fact once the last V is reached, it is hard to imagine a piece ending with anything other than I. This is not to say that I never goes down a fifth to IV; we have seen that I - IV6/4 - I can expand the initial tonic--and in the next chapter we will see that IV5/3 can can be used in the same way--but once V - I is encountered on a deep level with I as the final tonic, it is hard to imagine either V moving to anything other than I or that I will be followed by some other chord. Well, OK, there is the notable exception of "amen" harmonized by IV - I being tacked on to hymns which essentially have already been completed. But even though the "amen" is "tacked on," for the sake of argument, why does IV not anticipate a chord a fifth down during a final "amen?" That is, after hearing "amen" sung after a final tonic so that the sequence of chords is, say in the key of C: G - C (end of piece), F - C (harmonizing "amen")--why during the F chord are we not anticipating a B-flat or B root, both of which are a fifth below F? There are two answers, one for each chord:

So much for ending on I. Now, what prevents the circle progression from extending backwards in the other direction beyond vi? Sticking only to diatonic triads and root movement by descending perfect fifth, why are full vii° - iii - vi - ii - V - I progressions so rare? The reason for this has to do with the fact that the strength of movement from one chord to the next is not the same for each adjacent pair of chords. By "strength of movement" I mean the amount that the listener anticipates the next chord. Or to put it an other way, how much one chord makes someone anticipate the next. Specifically:

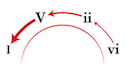

So there is a pattern. As we approach I in the circle progression, the strength of movement from one chord to the next gets stronger. This increase in strength of harmonic motion is symbolized in the cartoon above and by the image to the left by arrows which become bolder as they get closer to tonic. So there is a pattern. As we approach I in the circle progression, the strength of movement from one chord to the next gets stronger. This increase in strength of harmonic motion is symbolized in the cartoon above and by the image to the left by arrows which become bolder as they get closer to tonic.

And so that's it for this chapter. I hope you have enjoyed your journey around the circle of fifths, however short it has been! |

|

|

|

|

Comments? Click here. |